a Bengaluru

apartment

movement in space

Editors Smit Zaveri and Ayushi Saxena

Architecture often presents itself as seemingly immovable, still shelter. Yet, paradoxically, it creates profound movement. Movement of light entering a space, of wind travelling through it and of people moving within it. It also causes a larger movement, one that takes material from the earth and shapes it into objects of use. Hence, in its still form, architecture disturbs an existing state of balance within its context as well as in nature. We hoped to study these movements, and craft a space that develops a deep connection with its context.

The project involved renovating a 950 square foot two bedroom apartment that was recently acquired by a young professional. Nestled amidst trees in a central neighbourhood of Bengaluru, an Indian city once known for its slow pace and lush greenery, framed the context of the transformation. Furthermore, the changing needs of its new occupants—young professionals, and their lives in flux—served as the foundation of the design brief. This brief aimed to create an additional room for a home office while ensuring the apartment remained well-equipped for the routine needs of urban living: a space to entertain friends, a place to nurture hobbies, a shelter to house extended family, and a home to unwind in.

The existing apartment’s layout was fragmented, comprising nine poorly connected spaces with many inefficient elements. The layout included corridors for access and partitions for privacy for each room, resulting in unused space throughout the day. Several single-use rooms, such as the dining area and toilets remained vacant and closed for extended periods, denying neighbouring rooms the benefit of the views and ventilation these rooms enjoyed. The kitchen, despite its access to light, ventilation, and scenic views, was isolated from the rest of the house. The excessive emphasis on individual room storage led to unnecessary accumulation of rarely-used items, while overshadowing the potential for more efficient storage solutions. For example, a sizable common utility space, which could house essentials like shoes, bags, umbrellas, power backup, cleaning tools, and a washing machine. Similarly, a spacious pantry could have accommodated all kitchen supplies and appliances, eliminating the need for smaller, subdivided cabinets that tended to gather underutilised cutlery.

The prevalence of such inefficiencies is all too familiar in today's landscape, where many builders often overlook the importance of thoughtful spatial planning, and instead adopt principles of privacy and daily necessities that fail to resonate with the lifestyles and aspirations of the Indian populace. At a city-level scale, these inefficiencies add up and result in substantial wasted space. This phenomenon is unsustainable for growing urban centres such as Bengaluru, wherein neighbourhoods offering easy access to good public amenities are limited, and unaffordable for most due to their costly premiums. All together, such aspects added to the disconnect between the existing space of the apartment, and the essence and needs of its context. Reflecting back on the larger movement of architecture, of extracting materials wood and stone from the earth, perfectly attuned and playing their part in the intricate balance of nature, often moved and moulded by us into their new out-of-place forms.

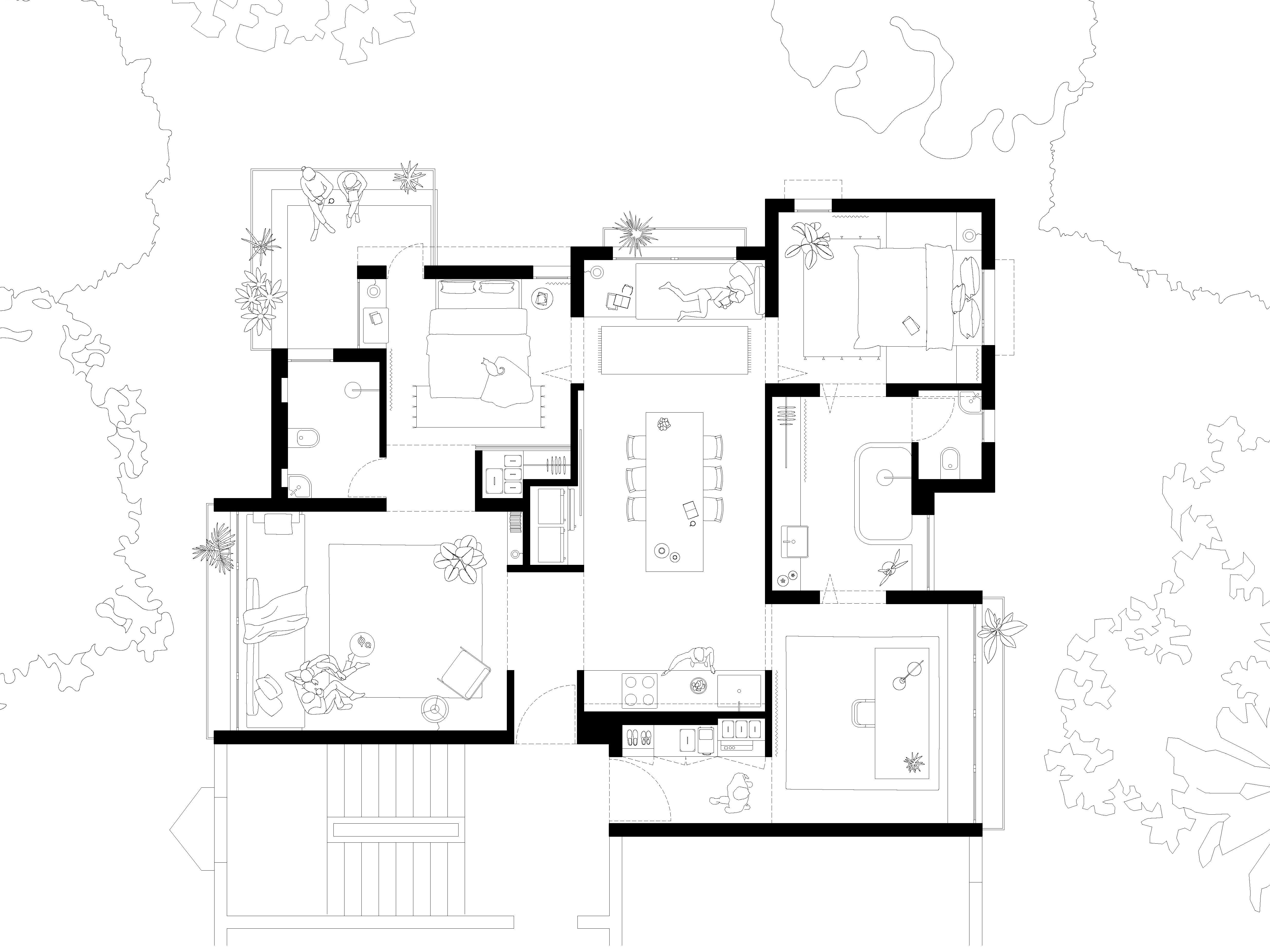

Our approach to planning the new layout questions the typical methods of dividing a home and creates spaces better suited to the resident’s needs. The revised layout consists of two blocks separated by a large communal kitchen and dining hall in the centre that houses the apartment’s main entry. Each block contains two rooms separated by a common bath. The first block is private, housing the main bedroom, home office on either side of a large bath, and the other is a public one comprising the living and guest bedroom separated by a guest bath. With the exception of the bathrooms, all rooms connect directly to the communal hall in the centre, eliminating corridors in the house. Every room has direct access to a bathroom, storage space, and the main entry through the dining hall, allowing each room to function independently, whether it's for work, sleep, or leisure. For added convenience, the new home office also features an additional external entry, providing easy access for professional purposes. This thoughtful layout transformed the apartment into a truly multi-functional space, capable of meeting the needs of a growing family—an invaluable feature in urban homes.

![]()

The design principles adopted for the new layout create efficiency without sacrificing functionality. We eliminated unnecessary partitions and tailored room sizes to their specific functions, for instance, a bedroom scaled only for peaceful rest, fostering a sense of simplicity in each space. This approach also afforded us additional floor area in each room which we could then redistribute to areas that could make better use of it, such as the communal hall and kitchen. Then, we placed walls only where they could support functional purposes like counters, seating and storage, ensuring minimal intervention and impact on the openness and flow of spaces. Next, by connecting all the spaces with large indoor openings we encouraged light, air and residents to move seamlessly through the apartment. Finally, to strike a balance between privacy and openness, we designed softer spatial divisions—floor-to-ceiling curtain dividers and large bi-fold doors offered adequacy and adjustability in terms of privacy as they could be kept open and tucked out of sight when not needed, maintaining the apartment’s open and inviting atmosphere.

As all spaces are connected internally and also to the communal dining with large openings, we decided to align these openings with each other, creating several axes that traversed the entire apartment. These axes increased the sense of spaciousness, allowed good ventilation, and let each room have access to the beautiful views its neighbouring rooms enjoyed. This design decision referenced traditional ways of dividing Indian homes, wherein communal courtyards were placed in the centre of interconnected living spaces—a piece of the outdoors which became a common space that filled the home with necessary light and air. One such axis runs through the living, kitchen, dining, and office, and opens out to the trees outside—four lively spaces sharing movement of light, wind, people and the greenery outside.

These aligned openings or thresholds became a characteristic motif of the design—spaces entered and exited through distinct wide thresholds, liminal spaces that opened and closed worlds. These transitional vestibules separate spaces internally as they are simultaneously stitched together, by offering glimpses of the spaces to come yet not revealing them entirely. Most significantly, these distinct separations imbued each individual space in this open layout with a distinct purpose and identity, like a meditative space for study gently separated, or a communal space for a meal brazenly linked to its surrounding rooms. This deliberate arrangement of pauses between spaces provided a structure to the experience of the apartment as a whole, evoking a sense of rhythm that guided one through the space.

Simpler thresholds such as entrances were reworked, formerly the two entrances for residents and service staff respectively were reconfigured to support an egalitarian use of space. One entry now became a welcoming chamber to receive guests, and the other, a private entry for residents and service staff alike into a galley-style utility corridor, backdropped by a treetop view. The more complex thresholds such as windows were also thoughtfully designed. The dense tree canopy all around provided natural shelter from the sun and rain, allowing us to create large, minimally protected windows that opened out to expansive views. These windows were then detailed with deep, comfortable wall-to-wall seating and railing planters. The concealed planters that concealed the pots of the plants seamlessly blended the greenery inside and outside, creating a serene spot for residents to enjoy their surroundings daily.

To further cement this connection with the outdoors which comprised various trees—jackfruit, coconut, avocado, mango, neem (Indian lilac), chikoo (sapodilla), eucalyptus, and almond—a material palette of warm, earthen tones was chosen. A terra cotta-toned cement floor helped ground the apartment in its natural surroundings, as if the soil upon which the trees stood flowed into the apartment. Coupled with the open layout of the home, this earthy floor gave the space an innate sense of calm and continuity. The pigmented cement was also used as plastering for some walls, shelves and counters, offsetting an otherwise neutral combination of off-white walls and curtains, plywood, and reclaimed teak. The metal railings and table frames were finished in sage green, echoing the natural scenery outside.

The custom furnishings and materials—the cement flooring, the furniture, the rugs—were made in collaboration with local workers, carpenters, and weavers, with materials reclaimed or sourced locally. This process that stepped outside the physical space of the apartment allowed a great level of synchronicity in every aspect of the design by establishing harmony between the space, the outdoors, the material, the work, and the worker.

The process of architecture is inherently intrusive; an energy intensive craft of removing materials from the earth, and shaping them for temporary shelter. This piece of architecture acknowledges this and hopes the displaced materials re-establish a deep connection with their new environment. It hopes that these materials, as they once did, continue to evolve with the changing needs and lives of its users, revealing the profound movement of architecture.

Back to photos ︎︎︎

The project involved renovating a 950 square foot two bedroom apartment that was recently acquired by a young professional. Nestled amidst trees in a central neighbourhood of Bengaluru, an Indian city once known for its slow pace and lush greenery, framed the context of the transformation. Furthermore, the changing needs of its new occupants—young professionals, and their lives in flux—served as the foundation of the design brief. This brief aimed to create an additional room for a home office while ensuring the apartment remained well-equipped for the routine needs of urban living: a space to entertain friends, a place to nurture hobbies, a shelter to house extended family, and a home to unwind in.

The existing apartment’s layout was fragmented, comprising nine poorly connected spaces with many inefficient elements. The layout included corridors for access and partitions for privacy for each room, resulting in unused space throughout the day. Several single-use rooms, such as the dining area and toilets remained vacant and closed for extended periods, denying neighbouring rooms the benefit of the views and ventilation these rooms enjoyed. The kitchen, despite its access to light, ventilation, and scenic views, was isolated from the rest of the house. The excessive emphasis on individual room storage led to unnecessary accumulation of rarely-used items, while overshadowing the potential for more efficient storage solutions. For example, a sizable common utility space, which could house essentials like shoes, bags, umbrellas, power backup, cleaning tools, and a washing machine. Similarly, a spacious pantry could have accommodated all kitchen supplies and appliances, eliminating the need for smaller, subdivided cabinets that tended to gather underutilised cutlery.

The prevalence of such inefficiencies is all too familiar in today's landscape, where many builders often overlook the importance of thoughtful spatial planning, and instead adopt principles of privacy and daily necessities that fail to resonate with the lifestyles and aspirations of the Indian populace. At a city-level scale, these inefficiencies add up and result in substantial wasted space. This phenomenon is unsustainable for growing urban centres such as Bengaluru, wherein neighbourhoods offering easy access to good public amenities are limited, and unaffordable for most due to their costly premiums. All together, such aspects added to the disconnect between the existing space of the apartment, and the essence and needs of its context. Reflecting back on the larger movement of architecture, of extracting materials wood and stone from the earth, perfectly attuned and playing their part in the intricate balance of nature, often moved and moulded by us into their new out-of-place forms.

Our approach to planning the new layout questions the typical methods of dividing a home and creates spaces better suited to the resident’s needs. The revised layout consists of two blocks separated by a large communal kitchen and dining hall in the centre that houses the apartment’s main entry. Each block contains two rooms separated by a common bath. The first block is private, housing the main bedroom, home office on either side of a large bath, and the other is a public one comprising the living and guest bedroom separated by a guest bath. With the exception of the bathrooms, all rooms connect directly to the communal hall in the centre, eliminating corridors in the house. Every room has direct access to a bathroom, storage space, and the main entry through the dining hall, allowing each room to function independently, whether it's for work, sleep, or leisure. For added convenience, the new home office also features an additional external entry, providing easy access for professional purposes. This thoughtful layout transformed the apartment into a truly multi-functional space, capable of meeting the needs of a growing family—an invaluable feature in urban homes.

The design principles adopted for the new layout create efficiency without sacrificing functionality. We eliminated unnecessary partitions and tailored room sizes to their specific functions, for instance, a bedroom scaled only for peaceful rest, fostering a sense of simplicity in each space. This approach also afforded us additional floor area in each room which we could then redistribute to areas that could make better use of it, such as the communal hall and kitchen. Then, we placed walls only where they could support functional purposes like counters, seating and storage, ensuring minimal intervention and impact on the openness and flow of spaces. Next, by connecting all the spaces with large indoor openings we encouraged light, air and residents to move seamlessly through the apartment. Finally, to strike a balance between privacy and openness, we designed softer spatial divisions—floor-to-ceiling curtain dividers and large bi-fold doors offered adequacy and adjustability in terms of privacy as they could be kept open and tucked out of sight when not needed, maintaining the apartment’s open and inviting atmosphere.

As all spaces are connected internally and also to the communal dining with large openings, we decided to align these openings with each other, creating several axes that traversed the entire apartment. These axes increased the sense of spaciousness, allowed good ventilation, and let each room have access to the beautiful views its neighbouring rooms enjoyed. This design decision referenced traditional ways of dividing Indian homes, wherein communal courtyards were placed in the centre of interconnected living spaces—a piece of the outdoors which became a common space that filled the home with necessary light and air. One such axis runs through the living, kitchen, dining, and office, and opens out to the trees outside—four lively spaces sharing movement of light, wind, people and the greenery outside.

These aligned openings or thresholds became a characteristic motif of the design—spaces entered and exited through distinct wide thresholds, liminal spaces that opened and closed worlds. These transitional vestibules separate spaces internally as they are simultaneously stitched together, by offering glimpses of the spaces to come yet not revealing them entirely. Most significantly, these distinct separations imbued each individual space in this open layout with a distinct purpose and identity, like a meditative space for study gently separated, or a communal space for a meal brazenly linked to its surrounding rooms. This deliberate arrangement of pauses between spaces provided a structure to the experience of the apartment as a whole, evoking a sense of rhythm that guided one through the space.

Simpler thresholds such as entrances were reworked, formerly the two entrances for residents and service staff respectively were reconfigured to support an egalitarian use of space. One entry now became a welcoming chamber to receive guests, and the other, a private entry for residents and service staff alike into a galley-style utility corridor, backdropped by a treetop view. The more complex thresholds such as windows were also thoughtfully designed. The dense tree canopy all around provided natural shelter from the sun and rain, allowing us to create large, minimally protected windows that opened out to expansive views. These windows were then detailed with deep, comfortable wall-to-wall seating and railing planters. The concealed planters that concealed the pots of the plants seamlessly blended the greenery inside and outside, creating a serene spot for residents to enjoy their surroundings daily.

To further cement this connection with the outdoors which comprised various trees—jackfruit, coconut, avocado, mango, neem (Indian lilac), chikoo (sapodilla), eucalyptus, and almond—a material palette of warm, earthen tones was chosen. A terra cotta-toned cement floor helped ground the apartment in its natural surroundings, as if the soil upon which the trees stood flowed into the apartment. Coupled with the open layout of the home, this earthy floor gave the space an innate sense of calm and continuity. The pigmented cement was also used as plastering for some walls, shelves and counters, offsetting an otherwise neutral combination of off-white walls and curtains, plywood, and reclaimed teak. The metal railings and table frames were finished in sage green, echoing the natural scenery outside.

The custom furnishings and materials—the cement flooring, the furniture, the rugs—were made in collaboration with local workers, carpenters, and weavers, with materials reclaimed or sourced locally. This process that stepped outside the physical space of the apartment allowed a great level of synchronicity in every aspect of the design by establishing harmony between the space, the outdoors, the material, the work, and the worker.

The process of architecture is inherently intrusive; an energy intensive craft of removing materials from the earth, and shaping them for temporary shelter. This piece of architecture acknowledges this and hopes the displaced materials re-establish a deep connection with their new environment. It hopes that these materials, as they once did, continue to evolve with the changing needs and lives of its users, revealing the profound movement of architecture.

Back to photos ︎︎︎

© 2021-25 KAAM. All rights reserved.